"The culture industry, in search for profits and cultural homogeneity, deprives 'authentic' culture of its critical function, its mode of negation - '[its] Great Refusal' (Marcuse, 1968a: 63). Commodification (sometimes understood by other critics as 'commercialization') devalues 'authentic' culture, making it too accessible by turning it into yet another saleable commodity" (p. 64).

Setting aside the question as to what actually constitutes "authentic" culture -- a question the Frankfurt School never answers satisfactorily other than to say that it pertains to the elite opposite of whatever mass culture happens to deem praiseworthy at the time -- and further setting aside the question of profit -- does the pursuit and acquisition of profit really rob art of its value or authenticity? -- this passage reveals much more than just an indictment against the culture industry's failure to live up to its mission to "stick it to the man." Storey's words (reflective of Adorno and his colleagues) hint at a profound paradox inherent not only in the culture industry, but in much of human history as well.

I call it the paradox of protest.

This paradox bears close resemblance to what Friedrich Hayek observes in The Road to Serfdom (1944). (Interestingly enough, Hayek, an Austrian philosopher, was a contemporary of the Frankfurt School.) In his seminal work, Hayek explores the phenomenon that transpires when the state, upon amassing great power, strives to bring about some seemingly well-intentioned end only to eventually come into direct conflict with that end, ultimately causing more harm than had no action been taken at all. Similarly, the paradox of protest occurs when someone or something, in protest against some perceived injustice or problem, gradually assumes the same qualities as, or becomes far worse than, the very thing against which it rose in protest.

In the case of the culture industry, this paradox appears to have occurred in that, as Storey writes, the very industry of artists and creators meant to protest capitalism and class structure has come to assume capitalist and class propensities itself, to the detriment of emerging artists and creators who fall outside "the established order." A disgruntled guitarist (Jack Black as Dewey Finn) laments this situation in the musical comedy, School of Rock (2003):

This phenomenon of "unintended consequences" (to use Hayek's words) permeates both history and mediated pop culture. Just to list a few examples... The French Revolution. The Third Reich. The Soviet Union. Idi Amin and Uganda. Michael Corleone and "The Godfather." Anakin Skywalker and the Sith. Even the citizens of Gotham in The Dark Knight Rises (2012) fail to recognize the full repercussions of this paradox when incited by a mad man wearing a mask (Tom Hardy as Bane):

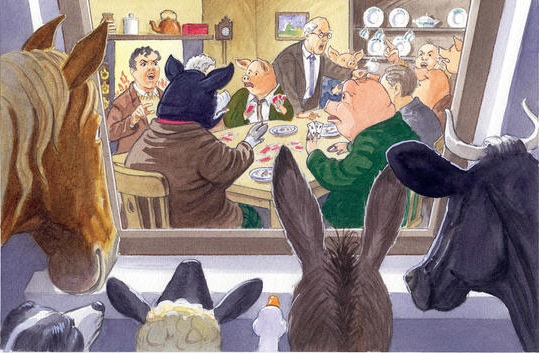

George Orwell, the not-so-subtle critic of totalitarianism (and another Frankfurt School contemporary), probably puts it most solemnly in the final line of his allegorical novel, Animal Farm (1945):

"The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which." QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION:

1. How does the paradox of protest affect the "authenticity" of mediated pop culture?

2. Is it hypocritical for the culture industry (Hollywood, etc.) to protest ideas it seems to embody or embrace itself?

3. What pop cultural examples of the paradox of protest come to mind for you?